Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Team Topologies: Organizing Business and Technology Teams for Fast Flow [Skelton CEO of Conflux and co-aut, Matthew, Pais coauthor of Team Topologi, Manuel, Malan Architecture Consultant a, Ruth] on desertcart.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Team Topologies: Organizing Business and Technology Teams for Fast Flow Review: Learn to thoughtfully design engineering org at scale - Great "API Design" for teams - You ship your org chart. Therefore, to fix shipping, fix your org first. This is often called the "Inverse Conway maneuver". Or, more verbosely, something like - "developing software is a socio-technical complex problem. We often naively focus on the technical part and only reactively look into the org part much later in the process. This should be turned around. Start with building the right org. In fact, the right org should be the very FIRST deliverable of a system architecture." All good, except there is no existing framework, empirical literature or large-scale study of "technical org design". That results in biased, reactive and unnecessarily nested, if not random, engineering orgs. To try to produce what we ought to, we lean into what we had in the past. That primarily results in huge communication overhead. This book methodically shows how to think and act on org design. It lays out four primary org types - value stream- (say, feature teams), enabling-, 'Complicated Subsystem- (say, databases or network), and Platform teams. It also shares three interaction modes these teams could work with each other - Collaboration, X-as-a-service and Facilitating. The 4x3 framework itself is a very powerful outcome from this. It also offers deep insights into composing, evolving and improving teams, and therefore the outcome of engineering orgs. Some key takeaways - -- Treat people & technology as a single carbon/silicon system. -- Hallmark of good org design is where the communication pathways converge with the org chart. Org-charts are top-down constructs, most human communication at the workplace is "lateral" - with their peers. Pay attention to this when taking an org chart driven decision, -- When a team's "cognitive capacity" is exceeded, the team becomes a delivery bottleneck. -- Conway's big idea really was this question - "Is there a better design that is not available to us because of our org?" An org has a better chance of success if it is reflectively designed. -- Orgs arranged in "functional silos" (e.g., QA, DBA, Security) is unlikely to produce well architected end-to-end flow. -- "Team assignments are the first draft of the architecture". -- "Real gains in performance can often be achieved by adopting designs that adhere to a dis-aggregated model". -- High performing teams, by definition, are long lived. Regular reorg for "management reasons" should be a thing of the past. -- Single team is typically upper bounded at a size of 15 people. That is the ceiling of people with whom "we can experience deep trust". -- Three types of cognitive load - Intrinsic, Extraneous and Germane. Germane is more domain specific - where value is added. Our goal therefore is to eliminate "extraneous cognitive load", e.g., worry-free, reliable build with automated tests should be a promise fulfilled. -- Rather than choosing the architecture structure (e.g., monolith etc), therefore a leader's objective function should be to manage the cognitive load of every team to achieve safe and rapid software delivery. -- High trust team management is essentially "eyes on, hands off". -- SRE teams are not essential, they are optional. The single most important "business metric" for SREs is "error budget". -- Designing platform team(s) is one of the hardest decisions. Left to engineers alone, Platform will be overbuilt. A 2x2 framework -- "Engineering Maturity" (High-Low) vs. "Org Size or Software Scale" (High-Low) is a good conceptual model to choose the right platform team model. e.g., for highly matured teams operating at a lower scale/size, individual teams could subsume platforms with right collaboration. Less matured orgs at a large size should lean toward the "Platform-as-a-service" model. -- 3 different dependencies between teams - Knowledge, Task and Resource. -- Only around 1-in-7 to 1-in-10 teams should be "non-stream aligned", i.e., one of the other three types - Platform, Complicated Sub-system or Enabling teams. -- "When code doesn't work...the problem starts in how teams are organized and how people interact." -- While we intuitively think of monolith as the "codebase", this mental model can be expanded. Monolithic Builds (when there is ONE giant CI, even with smaller services); Monolithic Releases (when different services still rely on one shared env for testing, say); Monolithic Standards (e.g., tight governance of tool/language/framework); Monolithic Workplace (e.g., Open-plan office). -- "Fracture Plane" (aka seam) is a good metaphorical framework to think about "how to divide teams". Such planes can be thought of from "bounded context" (i.e., business domain); Regulatory Compliance (e.g., PCI DSS/Payments); Change Cadence (e.g., annual tax vs. accounting modules); Risk (e.g., money movement, loan vs. dashboards); Performance (e.g., highly sensitive components vs. others); Technology (e.g., Rust, Golang etc); Geography (e.g., offshore vs. HQ etc). Traditionally, and unfortunately, we divide teams more on technology than on other, often more powerfully valid, dimensions. -- "If you have microservices but you wait and do end-to-end testing of a combination of them before a release, you have a distributed monolith". -- Intermittent collaboration is better than constant interaction. Collaboration leads to innovation, so do not suppress all human-to-human collaboration in naturally aligned teams, but pay careful attention to whether communication cost far exceeds collaborative benefits. Collaboration tax is worth it if the org wants to innovate very rapidly. Increased collaboration != Increased communication. -- Interaction modes between teams should be habits, i.e., a targeted outcome of org design. This is essentially what Jeff Bezos' famous "Teams only interact with each other with API or please leave" memo does. -- Be alert for the white space between the roles, gaps that nobody feels responsible for. -- Biggest change in last decade -- historically, "develop" and "operate" were two distinct serialized phases with one way arrow from develop to operate. The best orgs have a tight feedback loop from operating back to develop. Customers know the best! The "operate" phase emanates "bottom-up" signals from customers via logs, metrics and other data that developing teams must pay equal - if not more - attention to as it does from other "top-down" directives (say, from PMs). These are essentially "synthetic sense organs for the outside". -- Software is less of a "product for" and more of an "ongoing conversation with" users. This, to respond to users, MUST be an integral part of the development team's responsibility. This should not be forked out to a separate, isolated "BAU or Service Maintenance team". Excellent book - must read if you are leading teams that are growing. Review: Second Time Was a Charm! - Finally a resource that looks past the agile teams and supporting business facing only products by introducing Enabling and Platform teams. I read this book twice. The first time I read it I was working at another company and many of the teams were stream-aligned and there were platform teams, so the book was more validation rather than giving me new knowledge. I am now reading it through the lens of my new company and how they are organized and I am riveted. The business unit I am in is Conway’s law amplified and the book is giving me the words to be able to communicate the problems and why. I’m looking at the communications and dependency overhead and inside I am screaming “look at the software architecture!” And “break up the DB and Ops silo!” I myself am forming a platform X-as-a-Service team for Cloud-Native apps that includes CICD, containers, microservices architecture, data analytics services, observability services and using the book to help me design the teams. It is a well written and actionable book.

| Best Sellers Rank | #99,869 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #192 in Workplace Culture (Books) #884 in Business Management (Books) #1,182 in Leadership & Motivation |

| Customer Reviews | 4.5 out of 5 stars 2,922 Reviews |

N**A

Learn to thoughtfully design engineering org at scale - Great "API Design" for teams

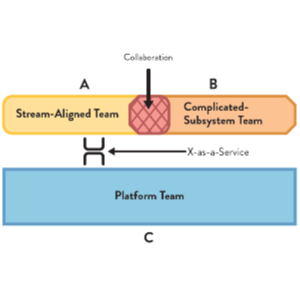

You ship your org chart. Therefore, to fix shipping, fix your org first. This is often called the "Inverse Conway maneuver". Or, more verbosely, something like - "developing software is a socio-technical complex problem. We often naively focus on the technical part and only reactively look into the org part much later in the process. This should be turned around. Start with building the right org. In fact, the right org should be the very FIRST deliverable of a system architecture." All good, except there is no existing framework, empirical literature or large-scale study of "technical org design". That results in biased, reactive and unnecessarily nested, if not random, engineering orgs. To try to produce what we ought to, we lean into what we had in the past. That primarily results in huge communication overhead. This book methodically shows how to think and act on org design. It lays out four primary org types - value stream- (say, feature teams), enabling-, 'Complicated Subsystem- (say, databases or network), and Platform teams. It also shares three interaction modes these teams could work with each other - Collaboration, X-as-a-service and Facilitating. The 4x3 framework itself is a very powerful outcome from this. It also offers deep insights into composing, evolving and improving teams, and therefore the outcome of engineering orgs. Some key takeaways - -- Treat people & technology as a single carbon/silicon system. -- Hallmark of good org design is where the communication pathways converge with the org chart. Org-charts are top-down constructs, most human communication at the workplace is "lateral" - with their peers. Pay attention to this when taking an org chart driven decision, -- When a team's "cognitive capacity" is exceeded, the team becomes a delivery bottleneck. -- Conway's big idea really was this question - "Is there a better design that is not available to us because of our org?" An org has a better chance of success if it is reflectively designed. -- Orgs arranged in "functional silos" (e.g., QA, DBA, Security) is unlikely to produce well architected end-to-end flow. -- "Team assignments are the first draft of the architecture". -- "Real gains in performance can often be achieved by adopting designs that adhere to a dis-aggregated model". -- High performing teams, by definition, are long lived. Regular reorg for "management reasons" should be a thing of the past. -- Single team is typically upper bounded at a size of 15 people. That is the ceiling of people with whom "we can experience deep trust". -- Three types of cognitive load - Intrinsic, Extraneous and Germane. Germane is more domain specific - where value is added. Our goal therefore is to eliminate "extraneous cognitive load", e.g., worry-free, reliable build with automated tests should be a promise fulfilled. -- Rather than choosing the architecture structure (e.g., monolith etc), therefore a leader's objective function should be to manage the cognitive load of every team to achieve safe and rapid software delivery. -- High trust team management is essentially "eyes on, hands off". -- SRE teams are not essential, they are optional. The single most important "business metric" for SREs is "error budget". -- Designing platform team(s) is one of the hardest decisions. Left to engineers alone, Platform will be overbuilt. A 2x2 framework -- "Engineering Maturity" (High-Low) vs. "Org Size or Software Scale" (High-Low) is a good conceptual model to choose the right platform team model. e.g., for highly matured teams operating at a lower scale/size, individual teams could subsume platforms with right collaboration. Less matured orgs at a large size should lean toward the "Platform-as-a-service" model. -- 3 different dependencies between teams - Knowledge, Task and Resource. -- Only around 1-in-7 to 1-in-10 teams should be "non-stream aligned", i.e., one of the other three types - Platform, Complicated Sub-system or Enabling teams. -- "When code doesn't work...the problem starts in how teams are organized and how people interact." -- While we intuitively think of monolith as the "codebase", this mental model can be expanded. Monolithic Builds (when there is ONE giant CI, even with smaller services); Monolithic Releases (when different services still rely on one shared env for testing, say); Monolithic Standards (e.g., tight governance of tool/language/framework); Monolithic Workplace (e.g., Open-plan office). -- "Fracture Plane" (aka seam) is a good metaphorical framework to think about "how to divide teams". Such planes can be thought of from "bounded context" (i.e., business domain); Regulatory Compliance (e.g., PCI DSS/Payments); Change Cadence (e.g., annual tax vs. accounting modules); Risk (e.g., money movement, loan vs. dashboards); Performance (e.g., highly sensitive components vs. others); Technology (e.g., Rust, Golang etc); Geography (e.g., offshore vs. HQ etc). Traditionally, and unfortunately, we divide teams more on technology than on other, often more powerfully valid, dimensions. -- "If you have microservices but you wait and do end-to-end testing of a combination of them before a release, you have a distributed monolith". -- Intermittent collaboration is better than constant interaction. Collaboration leads to innovation, so do not suppress all human-to-human collaboration in naturally aligned teams, but pay careful attention to whether communication cost far exceeds collaborative benefits. Collaboration tax is worth it if the org wants to innovate very rapidly. Increased collaboration != Increased communication. -- Interaction modes between teams should be habits, i.e., a targeted outcome of org design. This is essentially what Jeff Bezos' famous "Teams only interact with each other with API or please leave" memo does. -- Be alert for the white space between the roles, gaps that nobody feels responsible for. -- Biggest change in last decade -- historically, "develop" and "operate" were two distinct serialized phases with one way arrow from develop to operate. The best orgs have a tight feedback loop from operating back to develop. Customers know the best! The "operate" phase emanates "bottom-up" signals from customers via logs, metrics and other data that developing teams must pay equal - if not more - attention to as it does from other "top-down" directives (say, from PMs). These are essentially "synthetic sense organs for the outside". -- Software is less of a "product for" and more of an "ongoing conversation with" users. This, to respond to users, MUST be an integral part of the development team's responsibility. This should not be forked out to a separate, isolated "BAU or Service Maintenance team". Excellent book - must read if you are leading teams that are growing.

A**E

Second Time Was a Charm!

Finally a resource that looks past the agile teams and supporting business facing only products by introducing Enabling and Platform teams. I read this book twice. The first time I read it I was working at another company and many of the teams were stream-aligned and there were platform teams, so the book was more validation rather than giving me new knowledge. I am now reading it through the lens of my new company and how they are organized and I am riveted. The business unit I am in is Conway’s law amplified and the book is giving me the words to be able to communicate the problems and why. I’m looking at the communications and dependency overhead and inside I am screaming “look at the software architecture!” And “break up the DB and Ops silo!” I myself am forming a platform X-as-a-Service team for Cloud-Native apps that includes CICD, containers, microservices architecture, data analytics services, observability services and using the book to help me design the teams. It is a well written and actionable book.

J**N

Team-First, Explained

In our ever-accelerating world, one of the fundamental qualities of a good system is its ability to change and adapt. This requirement applies both to companies wishing to keep pace with competitors as well as to the software supporting their business goals. Within the context of software systems, one of the best practices is to compose them of independent, goal-oriented components. If the architecture achieves the so-called “low coupling and high cohesion”, there is a good chance that new business requirements would result in quick changes in a single part of the system, as opposed to the lengthy, costly and error-prone releases which plague the mismanaged software. “Team Topologies” demonstrates that the pressure for adaptability should not only restructure the computer programs, but also - and maybe even more importantly - the IT departments creating them. In my opinion it is an excellent work showing that IT should be thought of holistically, not as separate parts of technical code and people’s organization. The basic premise of the book - that the structure of software reflects the organization building it - is not new. Known as the “Conway’s law”, the insight is over 50 years old. But I believe there weren’t too many titles so cogent in explaining its ramifications. In conscious embrace of Conway’s inevitability, the authors propose a toolkit of organizational building blocks - the eponymous team topologies - to use within software development structures. A team is meant to be “the smallest entity of delivery”; it is teams that build software, not individual engineers. Any team, to be valuable, should be long-lived, purposeful and autonomous. Under such conditions it is truly able to take ownership of the part of the system it develops, to build knowledge and to work with a minimized risk of errors. There are four proposed team types. Most engineers should be expected to work within “stream-aligned” teams, focused on delivering value for the customers. Other teams take a more supportive role - delivering platforms for developers, building complicated subsystems which require specialized knowledge, or enabling stream-aligned teams to gather new skills and practices. Team structures can be nested e.g. a platform can be internally developed by its own stream-aligned teams. In addition to team types, the book describes expected interactions between teams depending on their type and role in the project. In my opinion, Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais make a compelling case that organizations applying the proposed approach - with team boundaries and responsibilities formed deliberately, which translates to proper boundaries and coupling within software components - can expect gains in the speed of delivery, as well as in software stability and employee morale. What is not stressed enough, in my opinion, is how difficult it is to design the aforementioned boundaries of responsibility of the team (and - by Conway’s law - of software built by it). From my experience it requires a deep knowledge of the business domain and is a daunting task for any large organization. The authors give a high-level overview of possible “fracture planes” (e.g. division by business domain, technology, customer type etc) but with only slight descriptions of how to find them precisely. In this regard, the book shows the end goal for how an IT organization should be structured without a detailed map on how to get there. It’s not a huge drawback, though, there is a lot of insights and knowledge to unravel nonetheless, I believe the book warrants multiple readings. I came to think that what “Team Topologies” propose is a convincing application of principles from agile and DevOps movements coupled with modern managerial practices, all while respecting Conway’s law. It is not a framework, though - I would rather call it a set of tools and insights to experiment with, regardless of any Named Frameworks™ your company might be using. All in all - I recommend this book to IT managers, architects, scrum masters and engineers interested in what happens outside of their teams. I guess it could be read by the business stakeholders as well, it is written in a way that won’t scare off non-technical people while giving insights on how IT could be more aligned with their needs. An instant classic if I ever saw one.

S**K

Conway's Law Revisited: Aligning Team and Architecture

Collaboration is good for innovation but increases cognitive load. And not all work is innovative. Managing this tradeoff between collaboration and focus is central to the theme of Team Topologies. Team Topologies presents some core patterns of team organization and communication that can help your team deliver effectively while minimizing (excess) communication overhead and maximizing necessary interactions. The authors emphasize that structuring your team isn’t simply something that you do once; you need to be alert to signs that your team (and architecture) need to be realigned. At first glance, this seems to be about “Conway’s Law,” and Conway’s observation that “organizations which design systems... are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations” is a central and recurring theme in the book. Team Topologies goes a bit deeper and presents some principles for defining and organizing your teams so that the teams and their communication structures support an architecture that makes sense (rather than the reverse). The book builds on various work around teams, teamwork, communication, and collaboration. While it did miss a few sources (such as [Thomas Allen](https://amzn.to/4cj0Lh8) for the role of office space in collaboration and [Organization Patterns](https://amzn.to/438d1N0) by Coplien and Harrison, it cites many essential works. Software architecture and technology problems can be challenging, but people architecture can be the more challenging of the two. Since teams of people build software, it’s important not to ignore the structure of your organization. While much work focuses on technology or technology, for complex systems, the interaction between people, processes, and technology is essential to understand since addressing issues on only one part might only be a short-term fix. Team Topologies can help you understand the role of the organization structure and dynamics in building good software architecture and data flow. If you want to understand how organization affects your architecture and how to work to align your team structure to get the architecture you want, this book is worth a look.

J**S

Software Architecture For Teams

If you're a busy CTO, the audiobook is just as excellent as the written one. Team Topologies highlights the problems your org chart is creating for your software's architecture (and as a result, your business). To remedy these problems, Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais offer a different perspective on org structure in the form of four fundamental team topologies: value stream aligned teams, enabling teams, platform teams, and complicated subsystem teams. The theory behind these team structures is chiefly built upon the premise of the Inverse Conway Maneuver, which "recommends evolving your team and organizational structure to promote your desired architecture." Ideally, this would require skilled software architects also be the architects of the teams in order to - for example - develop well-defined team APIs since software architects are already expected to be masters of API development. Additionally, the concepts of developing sensing organizations, using Domain Driven Design to identify fracture planes, and managing a team's cognitive load are dissected to explain how to effectively structure high-performing teams. If you have read and implemented the practices espoused in Project to Product, the Devops Handbook, and Accelerate but are still encountering communication bottlenecks and problems with scaling your existing team structures to meet product demands, then I highly recommend Team Topologies.

C**S

Provides definitions, lacks substance

I hoped for a deep dive into the tradeoffs and tension between vertical vs horizontal teams (stream aligned vs the other three in the book’s parlance). Instead the first section contains countless quotes that are nice, but platitudinal. Then they provide basic introductions of their team types, then provide contextless examples of structuring a group of teams. There was no second order analysis such as observing the side effects and potential weaknesses or strengths or how to balance or offset these. It served as an okay list of definitions but failed to go further or provide a deeper look at the inherent tradeoffs or push and pull dynamics. To make the feedback explicit, one example of missing substance was a complete absence of the observation that service teams (all 3 kinds) inherently introduce the risk that product teams can become blocked because they must wait for the service teams to build and deliver their tools and services. What happens when the tools team needs 6 months to get their stuff ready? Should the product team work around them? What happens when the product teams implemented 10 ad hoc versions of the tools they were waiting for in the interim? How should you unwind this? Which is preferable, how do you weigh these tradeoffs?

C**A

Great content, hard to power through

We read this book as part of a work book club and while there was a lot of good ideas and content, many found it tough to absorb and apply. Perhaps it was not the right read for us at the time but I definitely will continue to use this book as needed, just tough to sit down and read it consistently over a couple weeks.

E**K

Book arrived in good condition.

The book arrived in good condition. But I have not yet read it to comment on the contents. Recommended by CI youtube channel.

Trustpilot

2 weeks ago

2 weeks ago