Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

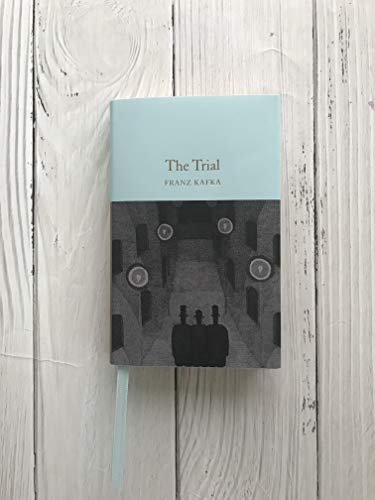

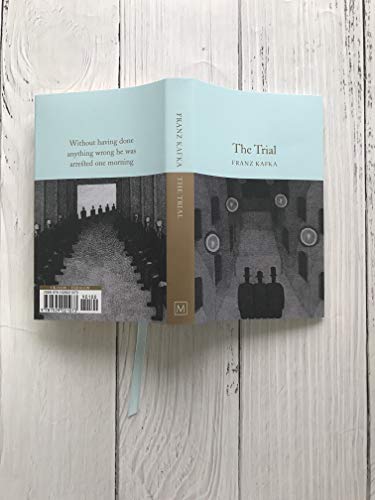

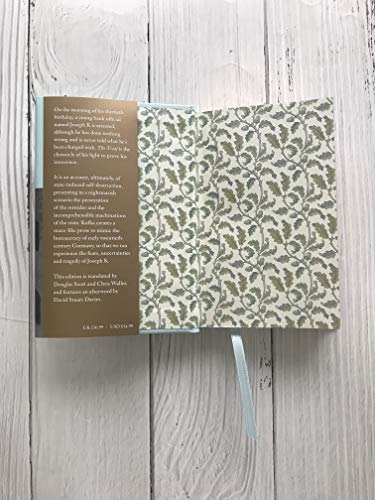

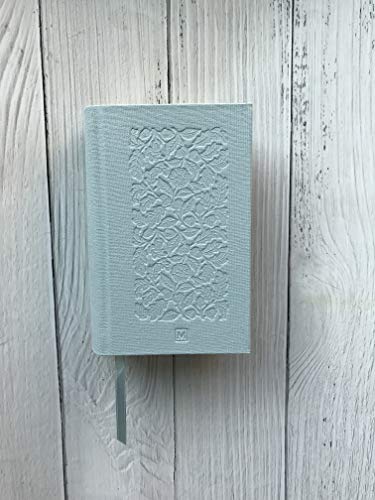

Buy The Trial: Franz Kafka (Macmillan Collector's Library, 241) by Kafka, Franz, Davies, David Stuart, Scott, Douglas, Waller, Chris from desertcart's Fiction Books Store. Everyday low prices on a huge range of new releases and classic fiction. Review: A book everyone must read! - It is not necessary to accept everything as true, one must only accept it as necessary Nothing speaks a more profound truth than a pristine metaphor… Funny, us, worming through the world ascribing meaning, logic and order to the dumb, blind forces of void. It’s all one can do to maintain sanity in the absurd reality of existence, but what is it worth? Are we trees in gale force winds fighting back with fists we do not possess? Is life the love of a cold, cruel former lover bating us on while only concerned with themselves? What use is logic in an illogical prison where the opinion of the masses reigns supreme? Franz Kafka’s The Trial is the world we all live in, unlocked through layers of allegory to expose the beast hidden from plain sight. On the surface it is an exquisite examination of bureaucracy and bourgeoisie with a Law system so complex and far-reaching that even key members are unable to unravel it’s complicated clockwork. However, this story of a trial—one that never occurs other than an arrest and a solitary conference that goes nowhere—over an unmentioned crime serves as a brutal allegory for our existence within a judgemental societal paradigm under the watch of a God who dishes out hellfire to the guilty. This is a world where man’s noose is only a doorway. The Trial is not for the faint of heart or fragile psyche yet, while the bleakness is laid on thick, it is also permeated with a marvelous sense of humor and a fluid prose that keeps the pages flipping and the reading hours pushing forward towards dawn. This is a dark comedy of the human comedy, full of the freeing chortles of gallow humor. Kafka’s nightmarish vision is the heartbeat of our own existence, chronicling the frustrations of futility when applying logic to the reality of the absurd, yet factual, nature of life. Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested. Seriously this is a book everyone should read. It teaches us about life in so many ways! Review: Is the Wordsworth the best British translation ? - Going by the translations of the novel I have read so far (I have three translations of this great novel: the Wordsworth, the Oxford World's Classics and the original Muir translation) the Wordsworth is the most readable and up to date. I'd avoid the Oxford translation; I couldn't get through it. The fluency of the translation is of some importance. Compare the following same sentence as translated by each: 1) K. was informed by telephone that next Sunday a short enquiry into his case would take place. (The Muirs) 2) K. had been informed by telephone that a brief investigation into his case would be held the following Sunday. (John Williams, Wordsworth) 3) K. had been informed by telephone that a short hearing IN HIS AFFAIR would take place the next Sunday. (Mike Mitchel, Oxford) The first two sentences work, the third is blunted by its clumsiness. Sentence version 3 is not idiomatic English, it sounds 'foreign', which can't be the intention. The Oxford version lacks an idiom .... Another example: "Some had brought cusions, which they placed on their heads so as not to hurt them as they pressed them against the ceiling." The reader needs to work out what these people are trying not to hurt - their heads or the cushions, so the joke is lost ... Kafka wanted a comic effect but this translation's vagueness dissipates it. I do not speak German nor have I the new penguin edition but the Oxford version stuggles to capture Kafka's grace and energy as a writer. The Williams version is the better of these two.

| Best Sellers Rank | 262,654 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) 342 in Jewish Fiction 793 in Fiction Classics (Books) 801 in Political Fiction (Books) |

| Customer reviews | 3.7 3.7 out of 5 stars (2,858) |

| Dimensions | 9.14 x 2.03 x 15.24 cm |

| Edition | New Edit/Cover |

| ISBN-10 | 1529021073 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1529021073 |

| Item weight | 1.05 kg |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 304 pages |

| Publication date | 1 Oct. 2020 |

| Publisher | Macmillan Collector's Library |

| Reading age | 18 years and up |

S**H

A book everyone must read!

It is not necessary to accept everything as true, one must only accept it as necessary Nothing speaks a more profound truth than a pristine metaphor… Funny, us, worming through the world ascribing meaning, logic and order to the dumb, blind forces of void. It’s all one can do to maintain sanity in the absurd reality of existence, but what is it worth? Are we trees in gale force winds fighting back with fists we do not possess? Is life the love of a cold, cruel former lover bating us on while only concerned with themselves? What use is logic in an illogical prison where the opinion of the masses reigns supreme? Franz Kafka’s The Trial is the world we all live in, unlocked through layers of allegory to expose the beast hidden from plain sight. On the surface it is an exquisite examination of bureaucracy and bourgeoisie with a Law system so complex and far-reaching that even key members are unable to unravel it’s complicated clockwork. However, this story of a trial—one that never occurs other than an arrest and a solitary conference that goes nowhere—over an unmentioned crime serves as a brutal allegory for our existence within a judgemental societal paradigm under the watch of a God who dishes out hellfire to the guilty. This is a world where man’s noose is only a doorway. The Trial is not for the faint of heart or fragile psyche yet, while the bleakness is laid on thick, it is also permeated with a marvelous sense of humor and a fluid prose that keeps the pages flipping and the reading hours pushing forward towards dawn. This is a dark comedy of the human comedy, full of the freeing chortles of gallow humor. Kafka’s nightmarish vision is the heartbeat of our own existence, chronicling the frustrations of futility when applying logic to the reality of the absurd, yet factual, nature of life. Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested. Seriously this is a book everyone should read. It teaches us about life in so many ways!

J**P

Is the Wordsworth the best British translation ?

Going by the translations of the novel I have read so far (I have three translations of this great novel: the Wordsworth, the Oxford World's Classics and the original Muir translation) the Wordsworth is the most readable and up to date. I'd avoid the Oxford translation; I couldn't get through it. The fluency of the translation is of some importance. Compare the following same sentence as translated by each: 1) K. was informed by telephone that next Sunday a short enquiry into his case would take place. (The Muirs) 2) K. had been informed by telephone that a brief investigation into his case would be held the following Sunday. (John Williams, Wordsworth) 3) K. had been informed by telephone that a short hearing IN HIS AFFAIR would take place the next Sunday. (Mike Mitchel, Oxford) The first two sentences work, the third is blunted by its clumsiness. Sentence version 3 is not idiomatic English, it sounds 'foreign', which can't be the intention. The Oxford version lacks an idiom .... Another example: "Some had brought cusions, which they placed on their heads so as not to hurt them as they pressed them against the ceiling." The reader needs to work out what these people are trying not to hurt - their heads or the cushions, so the joke is lost ... Kafka wanted a comic effect but this translation's vagueness dissipates it. I do not speak German nor have I the new penguin edition but the Oxford version stuggles to capture Kafka's grace and energy as a writer. The Williams version is the better of these two.

A**R

a pretty dark experience to read

😶The imagery is bizarre and claustrophobic...a pretty dark experience to read...but likely to prompt you to read more of Kafka

E**P

oh i LOVE this book!

Another book on my University reading list. I love it! It reminded me of Orwell's 1984, in that the main character is so introspective and verging on the mentally instable (that last point is good for debate!). I liked the way each chapter could almost be read as a seperate story - each one seemed very contained and condensed, and there seemed a clear break between each one. It was like reading something new, which made the overall read more interesting as there was always something new happening, and more people getting introduced. The story is written like the main character 'K.' is in a sort of dream, where strange things happen yet are enough based on realistic situations and things that it could be either dream or reality. It makes you think, and question. 'The Trial' focuses on concepts of questioning authority, the legitimacy of authority, obsession, guilt, isolation and bureaucracy. Very suited to the modern world.

L**S

Boring

I studied Kafka's Metamorphosis at university and loved the concept and the writing, but had never read The Trial. I gave up a quarter of the way through, but tried again, only to have to give up for good half-way through, as it's just the dullest book I've ever read (and I've read a lot!). The story plods along page after page with no variety of pace or emotion. It's pages of boring descriptions and paragraphs that never seem to end, but also don't even manage to say anything at all! Joseph K is a terrible character and I couldn't warm to him or his 'trial' (whatever it was... we never find out as far as I can tell). He meets lots of other awful characters in depressing locations, none of whom we care about particularly. Perhaps I missed the whole point of the book (or perhaps not), but sadly this one wasn't for me. Luckily I'd got it for next to nothing on my Kindle.

B**I

Great reading, you get emerged into the bureaucracy and the injustice, but you wouldn't find why, lofe itself is a bureaucracy.

R**Z

Back in university, I had a part-time job at a research center. It was nothing glamorous: I conducted surveys over the phone. Some studies were nation-wide, others were only in Long Island. A few were directed towards small businesses. There I would sit in my little half-cubicle, with a headset on, manipulating a multiple-choice click screen. During the small business studies, a definite pattern would emerge. I would call, spend a few minutes navigating the badly recorded voice menu, and then reach a secretary. Then my menu instructed me to ask for the president, vice-president, or manager. “Oh, sure,” the receptionist would say, “regarding?” I would explain that I was conducting a study. “Oh…” their voice would trail off, “let me check if he’s here.” Then would follow three to five minutes of being on hold. Finally, she would pick up: “Sorry, he’s out of the office.” “When will he be back?” would be my next question. “I’m not sure…” “Okay, I’ll call back tomorrow,” I would say, and the call would end. Now imagine this process repeating again and again. As the study went on, I would be returning calls to dozens of small businesses where the owners were always mysteriously away. I had no choice what to say—it was all on the menu—and no choice who to call—the computer did that. By the end, I felt like I was getting to know some of these secretaries. They would recognize my voice, and their announcement of the boss’s absence would be given with a strain of annoyance, or exhaustion, or pity. I would grow adept at navigating particular voice menus, and remembered the particular sounds of being on hold at certain businesses. It was strait out of this novel. When I picked up The Trial, I was expecting it to be great. I had read Kafka’s short stories—many times, actually—and he has long been one of my favorite writers. But by no means did I expect to be so disturbed. Maybe it was because I was groggy, because I hadn’t eaten yet, or because I was on a train surrounded by strangers. But by the time I reached my destination, I was completely unnerved. For a few moments, I even managed to convince myself that this actually was a nightmare. No book could do this. What will follow in this already-too-long review will be some interpretation and analysis. But it should be remarked that, whatever conclusions you or I may draw, interpretation is a second-level activity. In Kafka's own words: “You shouldn’t pay too much attention to people’s opinions. The text cannot be altered, and the various opinions are often no more than an expression of despair over it.” Attempts to understand Kafka should not entail a rationalizing away of his power. This is a constant danger in literary criticism, where the words sit mutely on the page, and passages can be pasted together at the analyst’s behest. This is mere illusion. If someone were to tell you that Picasso’s Guernica is about the Spanish Civil War, you may appreciate the information; but by no means should this information come between you and the visceral experience of standing in front of the painting. Just so with literature. To repeat something that I once remarked of Dostoyevsky, Kafka is a great writer, but a bad novelist. His books do not have even remotely believable characters, character development, or a plot in any traditional sense. Placing The Trial alongside Jane Eyre or Lolita will make this abundantly clear. Rather, Kafka's stories are somewhere in-between dream and allegory. Symbolism is heavy, and Kafka seems to be more intent on establishing a particular visceral feeling than in telling a story. The characters are tools, not people So the question naturally arises: what does the story represent? Like any good work of art, any strict, one-sided reading is insufficient. Great art is multivalent—it means different things to different people. The Trial may have meant only one thing to Kafka (I doubt it), but once a book (or symphony, or painting) is out in the world, all bets are off. The broadest possible interpretation of The Trial is as an allegory of life. And isn’t this exactly what happens? You wake up one day, someone announces that you’re alive. But no one seems to be able to tell you why or how or what for. You don’t know when it will end or what you should do about it. You try to ignore the question, but the more you evade it, the more it comes back to haunt you. You ask your friends for advice. They tell you that they don’t really know, but you’d better hire a lawyer. Then you die like a dog. Another interpretation is based on Freud. Extraordinary feelings of guilt is characteristic of Kafka’s work, and several of his short stories (“The Judgment,” “The Metamorphosis”) portray Kafka’s own unhealthy relationship with his father. Moreover, the nightmarish, nonsensical quality of his books, and his fascination with symbols and allegories, cannot help but remind one of Freud’s work on dreams. If I was a proper Freudian, I would say that The Trial is an expression of Kafka’s extraordinary guilt at his patricidal fantasies. A different take would group this book along with Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 as a satire of bureaucracy. And, in the right light, parts of this book are hilarious. Kafka’s humor is right on. He perfectly captures the inefficiency of organizations in helping you, but their horrifying efficiency when screwing you over. And as my experience in phone surveys goes to show, this is more relevant than ever. If we dip into Kafka’s biography, we can read this book as a depiction of the anguish caused by his relationship with Felice Bauer. (For those who don’t know, Kafka was engaged with her twice, and twice broke it off. Imagine dating Kafka. Poor woman.) This would explain the odd current of sexuality that undergirds this novel. Here is one idea that I’ve been playing with. I can’t help but see The Trial as a response to Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. As their names suggest, they deal with similar themes: guilt, depression, alienation, the legal system, etc. But they couldn’t end more differently. Mulling this over, I was considering whether this had anything to do with the respective faiths of their authors. Dostoyevsky found Jesus during his imprisonment, and never turned back. His novels, however dark, always offer a glimmer of the hope of salvation. Of course, Kafka’s universe is devoid of hope. Kafka was from a Jewish family, and was interested in Judaism throughout his life. Is this book Crime and Punishment without a Messiah? I can go on and on, but I’ll leave it at that. There can be no one answer, and the book will mean something different to all who read it. And what does that say about Kafka?

N**A

Era un regalo y le encantó. Llegó en perfecto estado.

D**O

He makes you think. It might not be his intention but that's the effect I have from a piece that should have never been seen.

G**H

Kafka’s The Trial is bleak, thought provoking, and darkly funny. Josef K.’s descent into a bureaucratic nightmare feels both surreal and painfully plausible. It is a world of dread where guilt is assumed, explanations evaporate, and systems grind on. The metaphor works on many levels. There are parts that remind me of Camus and Orwell. The novel’s unfinished state actually amplifies the gaps, abrupt turns, and unresolved threads that mirror the absurdity it’s critiquing. It’s sharp, oppressive, and eerily modern. 5/5

Trustpilot

1 month ago

5 days ago